What My $30 Cutting Board Taught Me About Design

We make pretty expensive stuff at Curio. Which means I'm supposed to evangelize about buying local, investing in heirlooms, and purchasing the last version of something you'll ever need. The truth is, I don't believe any of that, except in one very specific case.

Consider my beautiful $300 Boos block cutting board. It lives in a cabinet, brought out only for special occasions when I remember it exists. Meanwhile, the $30 OXO bamboo board gets daily use. It's lighter, easier to clean, has those chunky rubber feet that keep it from sliding around. Most importantly: I don't care about it. I can rinse it and leave it to dry. I can use it as a trivet. I can let my kids chop vegetables without hovering. It'll survive the abuse, or it won't. Either way, I'm fine. That OXO board has zero grip on my psyche because it cost me nothing emotionally or financially.

My 2014 Toyota RAV4 tells the same story. It's a cheap car with scratches and dings accumulated over years of actual use. Those imperfections aren't flaws, they're features. They grant me permission to throw lumber in the back, strap a Christmas tree to the roof, park in tight spots without anxiety. I wouldn't do any of that in a pristine Mercedes. Each upgrade in finish quality subtracts a functional capability. The nicer something becomes, the less willing you are to actually use it.

The pattern continues with my Japanese pull saw. It's missing a couple teeth now, which has somehow made it my favorite tool. I use it to break down cardboard boxes, cut PVC pipe, even saw boards directly over gravel when I'm too lazy to set up a proper work surface. Those missing teeth didn't diminish its utility, they expanded the range of materials and conditions I'm willing to subject it to. The damage liberated the tool.

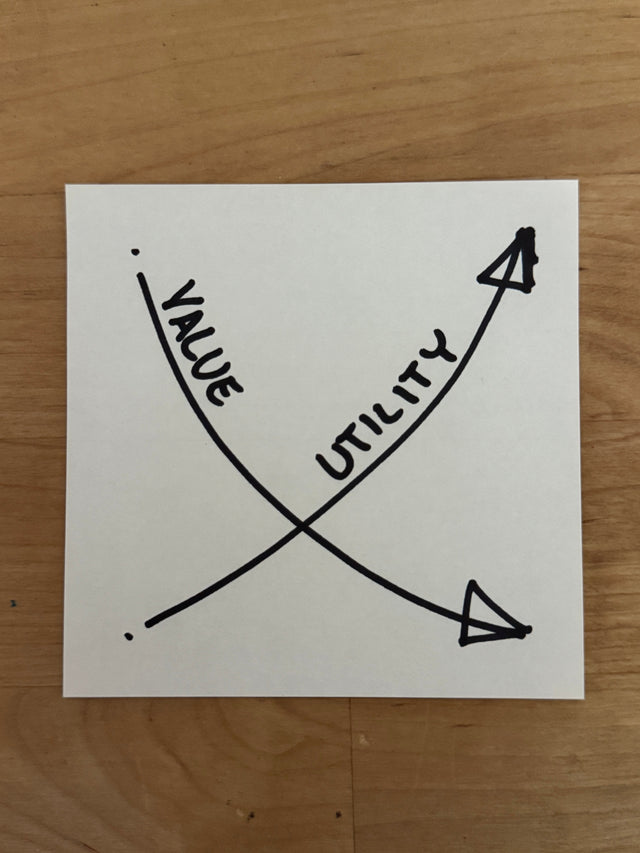

There's a principle here: functional objects become more useful as they become cheaper and more disposable. The freedom to not care unlocks their full potential.

But there's one critical exception: you cannot make art cheap. If it's cheap, it's cheap. Beauty, craft, and meaning require investment. Functional objects excel when stripped down to their essence and mass-produced. Art fails under the same conditions.

Which creates an interesting tension for what we do. Our puzzles aren't cheap, and they serve absolutely no practical function. They don't organize your desk, they don't help you cook dinner, they don't transport you anywhere. Their entire purpose is to introduce a problem into your life (a beautiful, compelling, irresistible problem).

By my own definition, that makes them art. Expensive, functionless objects that exist purely to be handled, admired, and puzzled over. And the better we can make them the better they are for you. So we aren't going to be cutting any corners any time soon.